Based on the title of this post, those of you who have studied or read a little about Machu Picchu may think this will be about the discovery of the site (HIram Bingham being its acknowledged discoverer). But actually, this is the Hiram Bingham I am referring to:

This is a luxury train, on the order of the Orient Express (I would imagine—and note that I believe the real Orient Express also uses a diesel locomotive these days). I suppose this is no mere coincidence, since the train is operated by a company called “Orient-Express”, which by the way also operates (i.e. owns) the hotels we stayed at in Lima and in Cusco—very extravagant and stylish, all three. We (or, rather, the tour company) booked the entire train for our journey down to Machu Picchu. This is what it looks like on the inside, starting with the dining car (one of two):

Beautiful wood and total attention to detail in the furniture and hardware and table settings and absolutely everything else. Mom and I had a table for two on the right side of the train, this was our home base for the journey. There were also two bar/lounge cars toward the rear of the train, they look like this:

The second one, the end car in the train, had a Teddy Roosevelt-style open platform in the back. I hung out there for a good amount of time, taking in the direct views and fresh air (punctuated by occasional wafts of diesel fumes) when Mom was dozing off to the lilt of the train during the early part of the ride:

A number of people came back to check out the open deck, and I ended up having quite decent conversation with some very interesting people, including an experimental filmmaker (who showed at Cannes), and the former CEO of a major US corporation. Also on the trip are successful entrepreneurs, investment bankers, sports team owners, etc.—in other words, home run hitters (for the most part). I suppose this should be obvious, given the expense of this tour, but I don’t think I’ve ever been immersed in such a group of high-powered folks. I’ll talk about the demographics and dynamics of our traveling companions in a later post.

Getting back to the train ride (which incidentally, is the name of one of my favorite childhood books [“Train Ride”, that is, not the first part], along with “Jake”, previously alluded to; I’ll have to find a guise for making reference to “Sylvester and the Magic Pebble” as well—oops, I guess I just did). Anyway, the train leaves from Poroy, which is 20 minutes outside of Cusco, and a few hundred feet higher in elevation (I think). There is also a station in Cusco, but the track between there and Poroy is susceptible to landslides and destruction (has been known to be out of commission for months at a time), so the luxury train departs from Poroy (can’t have falling rock landing on entrepreneurs, VCs, and sports team owners), unfortunately cutting an hour off the ride.

I just love traveling by train, I love watching the countryside go by, especially when it is simple (like this part of Peru), dotted with remnants of Incan and post-Incan history (I’ll show you a picture in a second). It is a little sad seeing some of the kids in well-worn, often tattered clothing, standing in their yards or on dirt roads as we pass through small towns, waving to the millionaires riding a shiny, fully decked-out train, sipping champagne (Moët, to be precise). I talked to some of the more sympathetic folks on the trip, who are also torn about this disparity (which repeats itself in some manner everywhere we go). We rationalize it by convincing ourselves that one of the primary sources of income in these areas is tourism, they want us to come and spend our money—they are better off for it—, but it’s hard to see the benefit in some of the places in the Cusco countryside, where it looks like they are really just scratching out a subsistence. I hope they are better off than I think and are satisfied with their living, but I don’t know (and fear they are not).

A cool part of the ride was reversing and switching to a narrower gauge track for the descent down to the Urubamba River (which is the river that flows down to Machu Picchu, and surrounds it on three sides). Here is a view from the rear platform of one of the switches in that process:

After the station at Ollantaytambo, where we picked up the members of the tour who had left earlier in the morning to see the remnants of the Incan town there, we were served a very nicely prepared lunch, with some nice wine choices. Most of the wines served thus far on the journey (except the sparklers), both on the plane as well as on land, have been from South America: Chile, Argentina, and Peru (at least when in Peru!!!). The wine is fine (though the reds tend to be tannic), it flows freely. The train clicks along smoothly and slowly, its rocking exaggerated by the narrower track (hence the askewity of some of the shots you see, both in and from the train).

The Urubamba River flows alongside the track (we cross over once), muddy and brutal in spots. There is a stretch of a few miles where there are rocks and holes and standing waves and crazy-churning and swirling water—our resident astronomer (one of the experts on the journey) claims that much of it is class 7 rapids, as difficult as rafting or kayaking can possibly get. I have no way of refuting or confirming.

We pass two interesting bridges. One of them is a small suspension bridge built upon the foundations of an original Incan bridge. Our steward on the train tells us that the Incan bridge was also of a suspension nature.

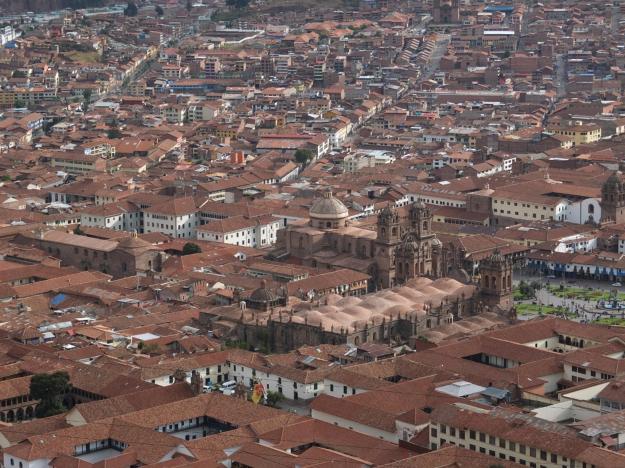

The second bridge is the one at the start of the Inca Trail, the original way to Machu Picchu, which climbs to fourteen thousand feet before descending to the site, and now a four-day journey to the site for the adventurous and fit tourist. We will see the end of the Inca Trail when we get into the location. After a three-hour ride from Poroy, the train takes us to the station at Aguas Calientes at the foot of the mountain on which the “citadel” of the Machu Picchu site is located. We get on small minibuses which take us up narrow switchbacks to the entrance of the site. Here is the view of the mountains on the opposite side of the river, when we get to the top:

The mountain on which the citadel is perched has sheer walls on all sides. The city and the agricultural terraces are situated between two peaks, Machu Picchu (“old peak”) and Huayna Picchu (“young peak”). Three is also a smaller peak situated to the left of Huayna Picchu (looking from the site), I don’t know the name, but we have dubbed it “Baby Picchu”. Baby Picchu is visible in almost all views that include its big brother Huayna Picchu.

For those of you paying attention, I left a teaser in my last post, saying that I only had four pictures of “Machu Picchu itself“. If you haven’t guessed by now, I meant Machu Picchu the peak, and not Machu Picchu the archaeological site (for which I actually have approximate a zillion and a half shots). If you don’t go out of your way to shoot the peak, it doesn’t show up, since it is so high above the city, you have to be looking upward to see it. I had a moment of panic after returning from the site and uploading my pictures to the computer, I wasn’t seeing a single shot that included the namesake peak, but as I said, I think I have identified four, always just incidentally included. For some inexplicable reason, I never thought to shoot it directly, even though we looked up at it many times, especially as the fog and mist drifted in and swirled around it after the brief rain shower we had, eventually masking the tip as it rose into the heavens. One of the shots is included in the headliner of the blog today (I will probably pull that shot somewhere into this entry when I change the header image). Challenge: try and identify the other shots with “Machu Picchu itself” in it. The first person to post the correct answer in the comments section will receive a souvenir from Peru (if I have one—or if not, then a souvenir from the airport in Indonesia or something).

It goes without say that visiting Machu Picchu is a stunning experience. I won’t able to express in words the wonder of the sights and the feelings evoked and the mystical convergence of the story and the setting and the engineering and the profound mystery of the unknown and unexplained—I can’t even make a decent attempt at it, given the limited time I have on the trip (we have a very full schedule, we are treated and entertained every hour of the day). So, I’ll just post a few pictures showing our path through the site, and say only a little something, I wish I could do more (both for yourself and for me and Mom), but that will have to wait until after the trip.

Here is the first thing you see upon entering the site, it is a set of storage houses in the agricultural area, built on the same terraces as the fields.

This is a combination of walls that have survived and other portions that have been rebuilt from the collapsed rubble, you can see the difference in color in this closer shot (the older being the darker grey, and newer being lighter with more brown in it).

We ended up climbing a set of steps hewn into the hill to the top of the terraces (near the guard house and the cemetary), which was a little bit of an effort, but when you get there and turn around, this is what you see:

There is no way to describe this in words, you just have to go there and see it for yourself. In the background is Huayna Picchu and Baby Picchu; Machu Picchu itself is at our backs. Here is the souvenir shot from that spot:

Climbing down the other side of the terrace, this is what we see looking back up at where we stood:

Here is a closer view looking down at the buildings within the city, as we descent into the main part of the site:

In the agricultural parts of the site, outside of the gated city walls, the terraces are broader and were farmable by the people at the time (though it is still incredible to imagine it when you see it). There were cantilevered steps jutting out from the end walls, some of which still survive, which would be sticking out straight toward you in this photo. Oh yeah, and there are llamas.

Going down from the urban portion of the site, where the slope is almost vertical, they built terraces as well, with sophisticated drainage systems (including hauling up tons of sand from the river 1200-1300 feet below) to control erosion and make the construction stable and robust. Was their engineering any good? Take a look, I’d say it’ll do ’til some other engineering comes along (which we ain’t seen yet).

Access to the city proper was controlled through a set of gates. This is a picture looking back at the one we entered through; take a look at the tightness of the construction and the size of the header beam.

There is so much stonework all around that you can see the “forest” and forget the level of effort and craftsmanship that went into it (the “trees”). Same thing when you look at pictures. In all of the photos that follow, please remind yourself to look at the variety of techniques and styles of the construction, and the elevated level of accomplishment.

Here is a picture of our guide group standing inside a room of some sort (not sure what sort).

At the start of the tour, they were sending us off twelve at a time with a guide; we were the last group to get rolling, with a headcount of just six. One guy was not feeling well a little ways in and went back to the Sanctuary Lodge just outside the entrance to the site (the premiere place to stay if doing a multi-day visit) to recover, leaving us with just five and our guide, Dagmar (on the left). Dagmar was great. Those non-open openings that look like boarded up windows are actually storage alcoves. The peak in the background to the left is the same as the first one posted above (across the river and the train tracks from the site), I don’t know its name.

Here’s Mom standing in an adjacent room. The roofs would have been thatched, similar to the reconstruction shown in the storage buildings (also above).

And though you can’t touch it and immerse yourself in it from where you are right now, remember, don’t stop looking at the detail of the stonework in these pictures:

Here is a picture of the “Temple of the Sun”, which had windows facing specific locations related to sun position on solstices and equinoxes. Note the Inca’s use of solar panels in powering the ancient site (a recent and unpublished finding), clearly they were even more advanced that previously ever thought.

Here is a view looking north across the plaza that divides the urban section of the site, showing some very creative architecture incorporating intact granite slabs that are part of the mountainscape. I don’t know whether this was a completed construction, or whether the Incas were intending to continue developing the granite to eventually replace the natural exposure with their iconic stonework.

The big tree in the shot is a very prominent presence in the large plaza lawn, which is otherwise complete flat and featureless. The tree is actually not from Incan times, but rather the accidental growth from a wooden stake used for marking a location, evidently still green, and left during earlier archaeological work in the 1930s or 1940s. It is now a trademark element of the site, but has nothing to do with the Incas who built the site.

This is a shot of a quarry from which they excavated the building blocks of the construction, I don’t know if there were others (there probably were, but I wasn’t always paying attention in class—my eyes and feet and mind wandering throughout the visit to the site, and often overwhelmed trying to imagine the culture and organization that went into the monumental scale and functionality and beauty of the achievement—so I can’t say).

The way the rock that has been carved out of the mountainside, and then further smashed or carved into pieces varying from boulder- to brick-size and allowed to tumble (or be placed) in their strewn-about locations, makes the materials part of the construction process come alive. I imagine this as an Incan Home Depot, where the master masons (or their apprentices) cruise the aisles shopping for the perfect stone (or stones) to complete their current project.

Just below the quarry is more terracing, presumably used to shore up the mountainside to prevent slides and deterioration. I don’t know if these terraces were also used for agriculture, but it wouldn’t be surprised if they were, given the enterprise and clear boldness of the people, despite the utter steepness of the terrain. Just beyond the terraces, you can see the type of terrain from which they were constructed. You have to let your imagination flow after taking in all of the information at the site—both details and panorama—to try and picture how they built the place and how they lived; the effect can be absolutely stupefying.

This is an obligatory picture of Intihuatana, which translates to “Hitching Post of the Sun” (a name I won’t use, since it has no ring to it whatsoever, more of a jarring clang).

This aligns with the sun (“Inti” being the sun god) in some particular way on the solstices, as more evidence of some spiritual (“heaven and earth”) significances of the site, rather than being just a vacation getaway for the rich and powerful among the Inca, as some have suggested.

Here are a few more shots, with no real commentary, showing the interaction between the construction and the striking setting and terrain of the site. Note the relative absence of people in the shots. I don’t know whether it is due to the off-season, or numbers control, or difficulty in getting to such a remote location, or whatever—but I felt like it was always possible to experience the inner spaces and see the larger sights without feeling like it was an overrun tourist checklist item.

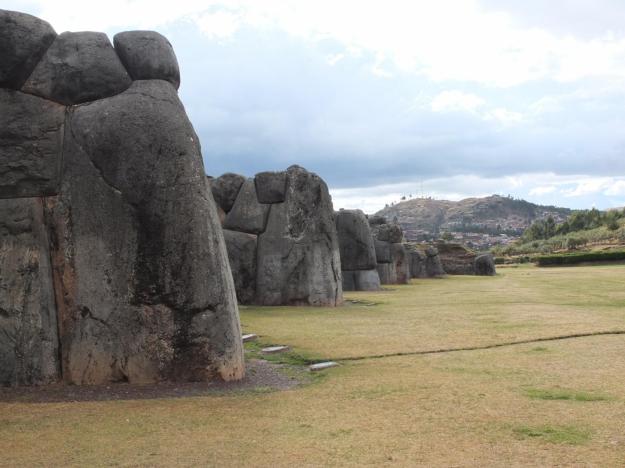

Here is one last look at some of the incredible stonework. The style of the cuts and precision of the assembly are so distinctly associated with Incan culture and ingenuity that whenever similar work is found, Incan attribution is easy to make (rightly or wrongly, as I will show in my Easter Island post, to come).

One thing that I truly struck me toward the end of our tour of the site, after strolling through all of the different areas—whether sacred, agricultural, or popular—, was the sheer amount of stone that had be quarried and cut and moved and precision shaped and placed, in order to build up the entire location. You could see this looking up at the face of the retaining walls of the extensive terrace work, and you could see this (obviously) in the elaboration of buildings and structures within the urban section. Subtly resisting attention is the massive effort it took to create all of the flat spaces in the site, all of the living surfaces (i.e. floors) and all of the communal spaces and plazas—each one requiring extensive leveling both in removing stone, as well as filling with the sand hauled up from the river (for drainage, as previously mentioned). But the vastness of the stonework is beyond description, here are a few shot attempting to capture the scale, each one pulling back from the previous (though not all shot pointing at the same place).

There’s no real way for me to adequately summarize the experience. It will take a while for me to let all of the thoughts—or better yet, the impressions—settle into place, and to be able to give verbal shape to the feelings. And each person will definitely have a unique and personal remembrance and interpretation of the history and culture and architecture and spirit of the place. No one will leave unspoken to. There were a group of hippies joining hands and chanting on the tier just north of the central plaza—rather cornball and trite in my book, you know, Stonehenge types—, but I grant them the freedom and the authority to do so. In fact, I believe it is granted by the spirit of the Incas, though I bet even the spirit of the Incas would wish they could keep the volume of the chanting down a bit (and little more in tune wouldn’t hurt either, neither would a shower and shampoo every once in a while).

I leave you with two parting shots (I mean, “photos”, of course). The first is our final view from the site before getting back into the minibuses for the descent back down to the Urubamba and the train, the same view that we first saw upon reaching the site hours earlier, only now in a different light.

And the second: after a nicely prepared dinner onboard the train, accompanied by decent South American wine and the lively banter of fulfillment among the members of the tour, this captures the wind down to a tranquil and nearly silent end of the ride back to Cusco, in our magnificent carriage.

This was a very good day.