Flying into Australia was a little intimidating. Rules, rules rules. Rules about what you can bring, and what you can’t. Rules about how to declare what you can bring, and how to declare what you can’t. Rules about what will happen to items you can bring, and what will happen to items you can’t. Et cetera. They also announced that we would have to take everything off the plane and bring it through customs, which was fine for me and Mom (we only had to additionally bring our “bagalini”), but for a few of the big shoppers it meant having to lug several additional bags stuffed with…well, stuff (good stuff, mostly from Peru). Much grumbling and griping. And lugging, for some.

We must have lined up 5 or 6 different places getting through customs and immigration in Brisbane. It was a hassle, but we got through okay with our regular luggage and our bagalinis (which incidentally, seems like a double-plural to me—I think it should be bagalino/bagalini, not bagalini/bagalinis). Not so fun for others, some who were forced to open multiple bags (in one or more of the 5 or 6 processing lines), or redistribute stuff between bags (camera lenses, etc.) to get under the 7 kilo per-bag carry-on limit (another rule that we never actually saw anywhere in the dissertation that was the rules publication).

After getting back to the gate for departure to Ayers Rock, Mom and I found an aboriginal art and crafts shop in the terminal. It was run by an organization that provides paint and materials to aboriginal artists, sells their works, and gives them back some of the proceeds. I had a couple of interesting small paintings (on unstretched canvas) in my hands, but time was short, and I ended up not buying because I didn’t want to make an impulse buy. It turned out to be the best opportunity in our visit to Australia to get a few works that I liked, and I missed it. Oh, well…

Back on the plane for a three hour flight to Ayers Rock, landing on just a tiny strip of runway in the desert. To call it an airport would be a big stretch. Beautiful smooth touchdown and braking by Captain Jon (apparently, Bravo Fox is specially equipped for such landings, with engines capable of massive thrust reversal and 8 brakes, which apparently is a lot). More on Captain Jon’s awesomeness at the end of this post. Anyway, the sun was getting low as we landed, see headliner photo (which is also serving double-duty as a teaser for Uluṟu photos to come).

Note that “Uluṟu”, which you all must know by now is the aboriginal name for Ayers Rock, is pronounced with the accent on the third syllable (“ṟu”), similar to kangaroo or Timbuktu, and not like micro-brew (first syllable) or tonkatsu (second syllable). Of course, that’s only when enlightened white Aussies say it (for instance, to a bunch of unenlightened tourists). When the Anangu (A’-na-nu) use it in a sentence, none of us born without a boomerang in-hand can possibly parse out a single syllable of any kind, let alone know where the freaking accent is.

The next morning, before getting anywhere near Uluṟu, we took a trip to The Olgas, which is a nearby rock formation whose Anangu name is Kata Tjuṯa (pronounced by our Aussie friends as “ka-da-JU-da”, adopting your thickest possible Crocodile Dundee accent when you say it—who knows what the real pronunciation is). They are actually part of the same national park, as apportioned by the Australian government. Here is a view of “the dunes”, which is the rock profile flanking the four Olga rocks themselves (only two of which can be seen as the left-most outcropping; the other two are hidden behind it).

Note that in the Anangu language, “Kata Tjuṯa” means “many heads”, which may actually include the “dune” rocks (not counted as Aussie “Olgas”)—in which case, there would be a clear conceptual misalignment, representative of the inherent cultural incompatibility between conqueror and vanquished everywhere (until the vanquished are actually just vanished).

Here is a closer view from a slightly different angle in which all four of the Olgas (though fewer of the many heads) are visible:

And here’s a view from the same spot of one of the many heads (not an Olga), which actually looks like a tortoise to me:

One thing that I really loved about the Australian outback where we were, was just the bush (how’s that for four W’s in a row?). Sometimes it was diverse in composition, sometime very uniform (as here), but it always seemed tranquil and timeless, and always represented hardiness to me, since it is just implausible that anything green could even grow out here. The wonder of the bush continues when you see areas scorched by wildfire, only to be reborn from the ashes. We saw bush in all phases of life and reincarnation, even in just this limited visit. I’ll show you an aerial view later, and explain why it is significant.

We came around to the backside (west side) of the Olgas. Here you can see all four of them (in white-people accounting, that is):

From there, we took a hike up the Walpa Gorge, between the southern two Olgas (right hand side, in the previous picture). Here is a shot of Olga number two, looking back out toward the mouth of the gorge:

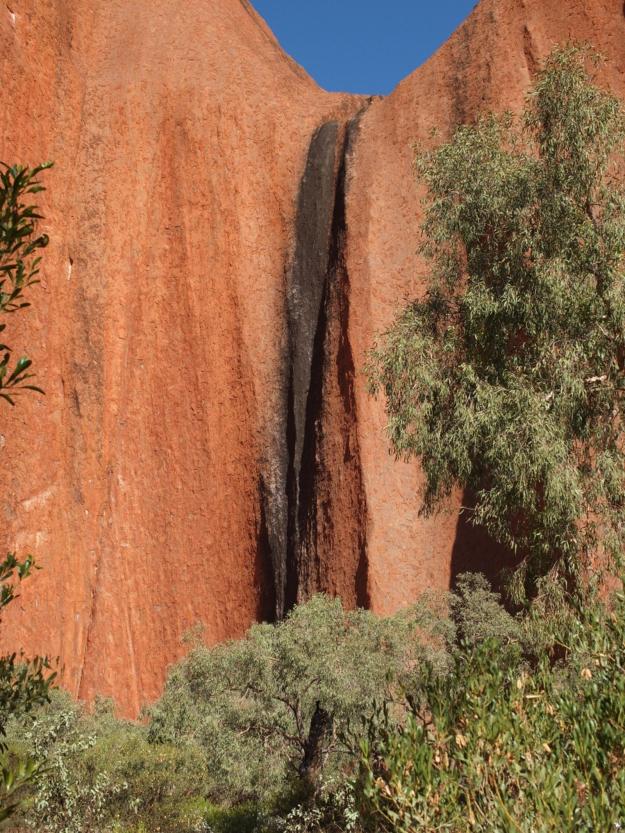

All of the pits and grooves and surface features are naturally produced by wind and water erosion, and the vertical black streaks are lichen and other plant matter that remain when waterfalls, formed by the few yearly torrential downpours, dry up. You will see more of these waterfall residuals in pictures of Uluṟu.

Speaking of Uluṟu, here’s Mom in a photo op, on our way to visit the big rock after lunch:

Here is a closer view, framed by more of the awesome outback bush:

We took a driving tour most of the way around the rock. The driver and guide (which are one and the same in Australia, the only such place during our trip, most likely because driving is reasonably civilized in Australia, and not a continually harrowing and life-threatening affair as in the other places we visited) explained to us that there were male and female “places” (meaning sacred places) around Uluṟu, where male and female activities were practiced. Not only are males not allowed to go to female places (and vice versa), the Anangu don’t even talk about their places and activities across genders. Many of the most interesting features around the rock—mostly caves and other sheltered areas—were such sacred places, either male or female, and the guide asked us not to take pictures of them out of respect for their culture. During this drive-around, the on-again/off-again picture-taking directives seemed rather forced and disingenuous, as if to inject some overblown reverence into the overall locale out of white man’s faux-remorse for invading and co-opting their most treasured territory, and relegating their sacred traditions to tourist attractions (rather than actually reverse the intrusion, and give them back their place and their ways). “This is a female place, no pictures…okay, now you can take pictures…male place, no pictures…okay, pictures…not now…now okay…”—it grew tiresome fast. Only later in the afternoon, after spending some time in the cultural center, and being led on a walk by Valerie (an Anangu guide), did I begin to understand how the concepts of sacred places and activities were related to the interdiction against photographs. I’ll get to that shortly.

First, the cultural center. We weren’t allowed to take picture inside there either. This seemed like more of the overblown reverence to me. I had wanted to try and buy an aboriginal painting (though it’s not as if I have any lack of stuff to hang, given all of the framed prints sitting on the floor stacked against the wall in my house), after getting hooked by the smaller pieces at the Brisbane airport. The iconic dot paintings that depict animals and people (at least their butts, represented by U-shaped lines) and specific surface features, like rivers and water holes, don’t really do it for me. They’re too primitive, in a crafts-project kind of way, for me and my snooty post-Renaissance western-European sense of aesthetics. The ones I like are more abstract, and represent the overall texture of a landscape, or even just a concept (such as dancing) without any discernable pictorial mapping. I hate to say it, but they’re just more western looking.

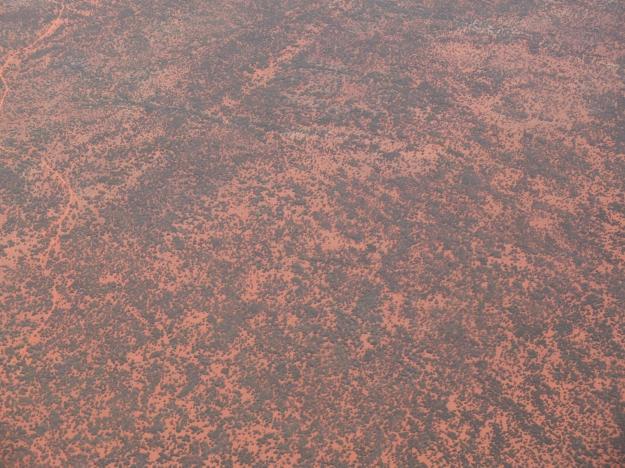

Painting is actually a somewhat-recently acquired art form for the aborigines, with the introduction of modern canvas and paint by westerners fifty or so years ago, though many of the designs and symbols they use are not only traditional but downright ancient. It also seems like some of the abstract expressions that I responded to were only brought about with aboriginal exposure to airplane travel and viewing the land from above (or possibly, photos from above), unless the artists are truly able to envision the larger texture of the land purely based on their ground-level experiences of the land. Though none of the paintings looked anything like this (or any other aerial shot) in explicit terms, some of them had an incredible similarity of emotional quality.

I saw several paintings, generally large, that I was considering buying—or at least, thought I was considering buying—, but there really was not enough time to fully absorb the images and decide whether I would actually want to hang them. Too bad I can’t show pictures of them, but I honored the request not to photograph. In the end, I wasn’t sure whether I loved any of the paintings more than I actually just loved the idea of buying a painting (and it wasn’t so much about whether to spend $1000+ on one, since I really did intend to support the aboriginal community in some way, after Brisbane), so I did the cowardly (and wise) thing and walked away with regret.

One of the canvases I really liked was meant to depict a women’s ceremonial dance. But because the artist did not want to reveal things that were private to women and private to her people, she chose to make it a purely abstract representation, with verticals lines of red and white and blue and black, with jagged edges and a very tribal feel. It showed nothing of the ceremony (that I could see), but must have been her way of conveying a spiritual essence of it. This was a lesson in the sanctity of their knowledge and their ways that I was able to personalize. This jealous protection of their secrets humbled me, and I had to accept my alienation from it.

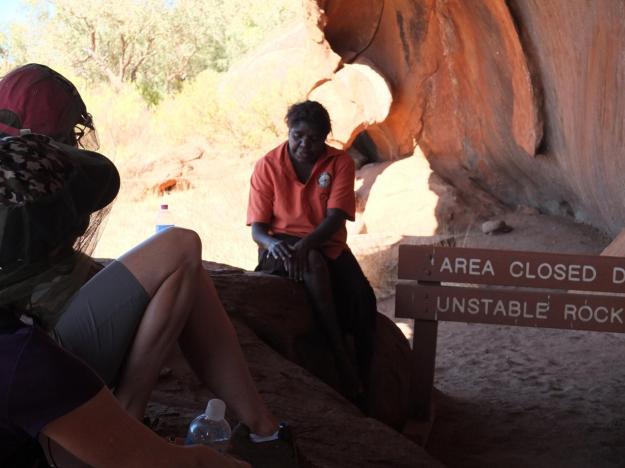

After the cultural center, we went on the Mala Walking Tour with Valerie and John, a white Australian guide who acted as translator. As we walked along a trail at the base of the rock, Valerie told the story of how the Anangu people came to this area, speaking in an unparseable mumble, which John appeared to actually translate (as opposed to just telling the story his way in English). This whole act of mumble-translate-mumble-translate started out feeling very staged and awkward to me (John said she was very shy), but at some point, Valerie seemed to loosen up and deviate from a purely rote narration, and the interaction between Valerie and John (and by extension, us) became easier and more interesting.

Valerie showed us a number of caves, some of which were too sacred for pictures, but some not. Each one had a story and a place in the history of the Anangu people.

In one of the caves, some of the Anangu ancestors were trapped by a beast, and ended up frozen in the walls. These ancestors protect the current Anangu people when they use the cave now.

In another cave, Valerie showed us what appear to be primitive drawings.

It actually turns out that this is actually not art, but knowledge passed down from grandfather to grandson (by the way, I’m a little fuzzy on how Valerie was able to show us this place, since it is a male place). The elder communicates the knowledge when the time is right, and in the way that is right, and the youth accepts it as presented, without questioning. This is also the manner in which Valerie recounted the Mala story to us (with the help of only John’s voice).

At one point, we passed another walking group, who said that they had just seen a wallaby nearby. Valerie said, with great assurance—even without having seen the animal—that it was there because of the water hole. We saw no signs of water or moisture anywhere about—it was 100 degrees out and totally parched. She took us to a sheltered area with a steep sandy floor and told us to watch (though, no pictures). She took a short rugged stick and started digging in the sand at the base of the rock. She dug purposefully and with a clear technique, and after about five minutes, the sand became moist. She kept digging, with a different motion and a slower rhythm, and soon water started pooling the hole. She cupped with water in her hand and splashed it on the wall to show us it was real, and the pool refilled itself as she scooped out each handful.

As I have been alluding to, the Anangu generally view photographs of themselves and their sacred places and activities as taking away from their spirit, but Valerie told John to tell us that it was okay to take pictures of her, but not too many. I shot this one surreptitiously, so as to take away as little of her sprit as possible.

There was one other interesting interaction at the water hole. After Valerie found the water for us, John had a brief exchange with her, and then she walked a little distance away. John told us of how the Anangu men would hunt animals who can to drink at the water hole, taking only what they needed, and the technique for assuring that the animals would return. I asked John if he had to ask Valerie’s permission to tell the story (which is what it seemed), and he said yes. Interestingly, I think she allowed him to tell it (and not tell it herself) because she felt it was his knowledge to impart, his story to tell. To me, this sequence said a lot about the rigidity of the gender roles, as well as her acknowledgement of his acquired acceptance by her people and belongingness the land. Note that John had to learn the language and the ways by living within the Anangu community, there are no classes or lessons or other ways to acquire the knowledge.

During the walk, it was also extremely interesting to get a closer look at the rock surface, which was actually fairly rough and abrasive, but very regular (it is said that it you fall from the top, you will be skinned alive before being killed by the impact).

As with the Kata Tjuṯa formations, Uluṟu exhibited a number of areas where water runs down following large storms and leaves traces of plant material.

Note the presence of many smaller caves and areas of shelter in these last two photos, as well. Uluṟu, the rock, is indeed awe-inspiring from any angle and any distance, the entirety of it as well as all of its special and secret places.

One last shot from the Mala walk: can you imagine what this would look like after a big rain?

At the end of the tour, we said “Palya” to Valerie, which means “thank you”, but also “hello” and “good bye” and “peace” and “good wishes” in general—much as “Aloha” in Hawaiian or “Shalom” in Hebrew. I mentioned to a fellow member of the tour that we Americans don’t really have a word for such a simple and beautiful—and perhaps, ancient—concept; that we’re basically too damned literal in what we say. She suggested, “how about ‘peace be with you’?”, but I don’t think that’s quite it. First of all, it’s really only used in church, and second of all, it doesn’t really convey all of the meanings. Perhaps closer is just “peace”, at least as it was used by hippies during the 60’s, but not anymore. Now it seems to be more prevalent as a defensive measure, like “don’t taze me, bro”.

That night, we were treated to a “Sounds of Silence” dinner out in the desert, which featured champagne and cocktails on a little plateau looking out at a gorgeous view of Ayers Rock at sunset, dinner accompanied by a didgeridoo and about a billion-and-a-half grotesque and dim-witted flying insects attracted to the table lights, and a post-dinner tour of the clear and moonless southern sky. Very easy to see unaided, and totally awesome, were an upside down Orion, the Pleiades, the Orion Nebula, Alpha Centauri, and both the large and small Magellanic Clouds, among a host of other glowing objects.

Some of us also woke up at 3:30 the next morning to see the early morning sky, before heading out in a larger group to catch at sunrise at Uluṟu. Everybody’s favorite is of course the Southern Cross (really just called “Crux”, or “The Cross”), but Alpha Centauri (our closest neighbor at 4.3 light years away) was also still prominent as the lower of the two stars in the bottom of this picture (sorry for the crappy photograph, I had neither a tripod nor a clue as to how to shoot stars).

The scene at the sunrise viewing location was quite a circus. Apparently, this is a very popular thing to do, there were many, many tour buses out there before the dawn, each with a hastily erected table with coffee and pastries. The viewing platform looked like this:

Here’s the pre-dawn light silhouetting the clever and stalwart desert trees (more shots of them in the light, below):

Note the sliver of a moon; this was just two days before the total solar eclipse that we were scheduled to see in Port Douglas.

And here’s the actual sunrise through the bush:

It was actually a little hazy that morning, so we didn’t get the classic rich red ochre Ayers Rock shot that you see in the calendars. Some of the people were disappointed, but seriously, you can’t expect to get that every day. Here are two views of the colors and the shadows changing as the sun rose on that particular day:

I personally was not disappointed in the least. I saw the conditions and the changing light, both at Uluṟu and at Kata Tjuṯa, as Monet would have: with receptiveness and serenity and wonderment at the uniqueness of the moment.

I mentioned the desert trees in the area, I don’t know what species they are, and recall only scant details of their amazing survival techniques, but I do know that they are both distinctive as species, and individual in their looks. If I had time, I would shoot a whole bunch of them and arrange the prints in a grid for display. For now, these two will have to suffice:

As we flew out of the Ayers Rock area that day, Captain Jon treated us to a low and slow fly-around (6500 feet, at just under 200 miles per hour) of both Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa. He circled both rock formations twice, once for each side of the plane. I’ll let the pictures do the talking to close out this post.