This is a post I have been looking forward to writing for a while, since it covers a long(ish) personal quest to get reacquainted with—and perhaps even acquire—several works of art that captivated me at first glimpse more than twenty years ago. Along the way, I have evolved and deepened (I would like to think) my appreciation for contemporary art and artists, through a continually developing interest, exploration, conversation, thought, and perhaps just the passage of time (which means, of course, “growing up”). Here’s the story, which is also long(ish)—I’ll try and keep it manageable.

Acquaintance

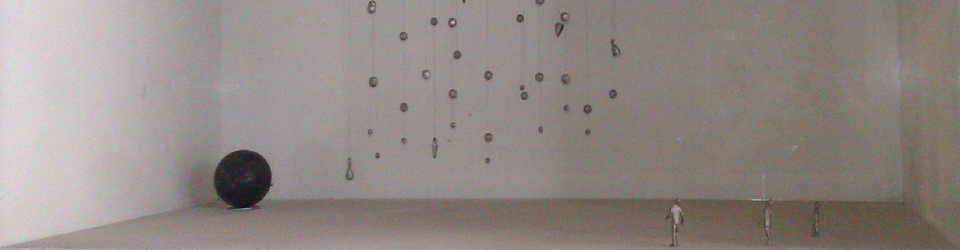

In 1990, my friend Alberto took me to his father’s studio in Chicago one night. His father is Virginio Ferrari, who is a well-known sculptor, with many public and private pieces around the world, especially around Verona (where he is from) and Chicago (where he moved to in the 1960s). As we entered the studio, even before turning on the lights, I could see shapes and figures looming and lurking—perched, posed and reposed—barely revealed by the dim ambient street light leaking through the windows. And then with the lights switched on, I could see their faces and torsos, their skin and bones, their stances and personas—of steel and aluminum and bronze—finished pieces, works in process, or some of them only ideas just starting to take shape.

I walked slowly among the pieces—some of which looked and reached outward to us and to each other, some of which sat introverted in their spaces—treading a path through constructed spaces, stoic monuments, and moments captured in time. I wasn’t able to say how much of geography and landscape of this abstracted world was purposeful and how much was perhaps chance arrangement. In either case, it seemed the authentic condensation of an artist’s perception, interpretation, and expression of the real world.

We probably spent the better part of an hour there. In addition to the maquettes and completed sculptures, there were drawings hanging high on the walls and in bins. I knew of the sculptures previously, having seen several of Mr. Ferrari’s public works around Chicago (and private works in their house), but these drawings were new to me. They represented working sketches of sculptural works and elements, but also abstract ideas and studies on form and color and texture. I was blown away. The studio made such an impression on me that I was unable to go to sleep that night. Instead I stayed up mulling and reliving the visit, and ended up writing a four-page poem called “Studio by Night”.

Reacquaintance (and new discoveries)

In late 1991, I moved back to California, and my interaction with my Chicago friends (shamefully, on my part) reduced to a mere trickle. As my interest in art grew, I would periodically ask Alberto to see if his father was willing to sell any of his drawings. The answer was always a little vague, until just before a visit back to Chicago in May of 2012. I asked Alberto about the drawings again, and this time he said his father would be happy to oblige. During the trip to town, Alberto and I went to the studio (along with our friend Fred), which had at that point moved to Wabash in the South Loop, to look through the drawings (as well as the sculptures, of course). It was amazing, flipping through drawer after drawer of flat files.

In addition to the drawings, some of which I had remembered from before, I discovered a beautiful set of prints: aquatints and etchings, in brown and black and red and green and blue. The prints were proofs of images done for an illustrated fine press edition of poems (“Mottetti”) by Eugenio Montale, published by a company called Raphael Fodde Editions. Also in one of the drawers was a copy of the book (gorgeous book), and several letters discussing the preparation and publication of the book, addressed to Virginio Ferrari, from Raphael Fodde.

As we explored the paper works, Alberto took pictures on his phone of the ones I said I was interested in. We also pulled out, separately, several drawings and several prints that particularly impressed themselves on me. There were so many fascinating ideas and themes and set of works that it was difficult to choose. It was unbelievably exciting.

Minor Interruption

The going was slow, since there were so many works, and it was worthwhile looking at every single one that we could. With many more drawers of drawings (and who knows what else) to go through, Alberto remembered that he had to feed to parking meter outside. He said Fred and I could stay and continue working through the portfolios, but we said we would come down with him. We went out and fed the meter, but when we got back to the studio, we couldn’t get back in the door. The lock had broken, and they key was not working. We had to leave, task undone. Me, disappointed, but at least gratified at having started the process. It was okay, though, since I was sure that (with Alberto’s assistance) I would be able to complete the quest, at some point.

Fulfillment

Sure enough, a year later, I was back in Chicago (what’s one year, when it’s been a twenty-year journey?), and back in the studio (moved again, this time to Bridgeport). I was able to pick out several drawings that I really wanted (six, to be exact, across two different series of works). In the process, I was able to start up a very nice conversation with Mr. Ferrari, who I had known only incidentally when I was in high school (mostly greeting in passing, when visiting Alberto at his home), but never spent any time really talking to. He was gracious enough to let me purchase the works that I selected.

The Artist

Virginio Ferrari is one of the “true artists” that I spoke of in my Words and Art posting. He is a lifelong, and full-life, explorer and philosopher and communicator through his art. His art must be able to interact with the people it is intended for, as well as with the space in which it is installed. He insists on having a hand in every construction and every installation, otherwise the art will not feel (yes, I’m saying art has feelings!!!), and be felt, in the right way.

His works are often simultaneously beautiful and enigmatic and powerful and touching. Pieces from some of his periods are strongly organic in form and character. Other works and other periods appear to be purely geometric, but to me there always seems to be an inspiration and a spirit at its core that inescapably comes from nature. The pieces always seem to represent an emotional or corporeal essence, or a lifecycle process, or a relationship between entities.

And now, finally, to the art.

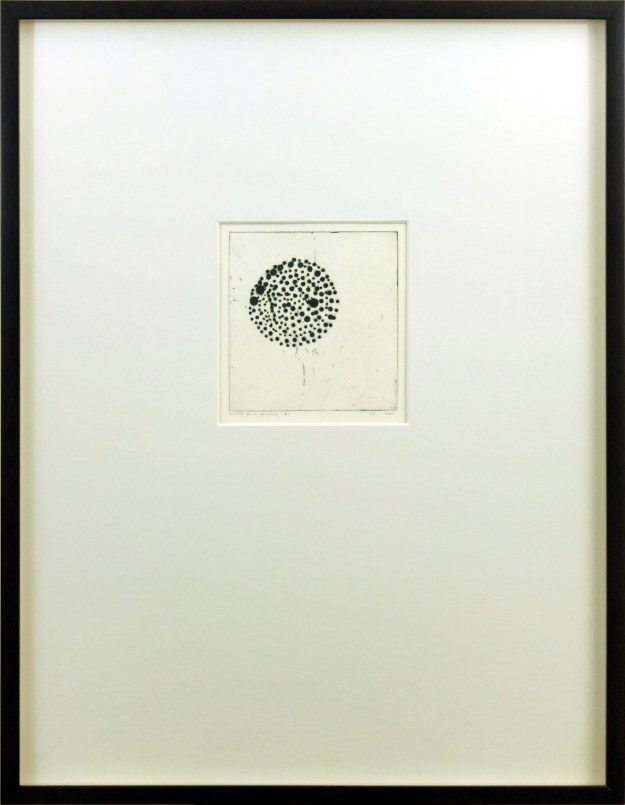

Gestos, 1977

I’ll close this post by showing three of the pieces from my quest. These are from a larger series of charcoal-on-paper drawings that Mr. Ferrari calls Gestos (“gestures”, in English), done in 1977.

These are horizontal works on paper, but I floated them in vertical frames (30” x 36”) because I wanted to hang them as a set (in my dining room). I find that these pieces have a strong tie-in with Virginio Ferrari’s sculptural work, yet I see in them new clues to some conceptions or aspects of the sculpture that are obscure, or in some cases, completely hidden (whether or not by intent).

These drawings show circular forms, as well as apparent surfaces (curved and straight) that meet, either intersecting or tangentially melding and supporting each other. Through the years, Mr. Ferrari has realized these kinds of geometries in three dimensions, on a large scale (as well as smaller scale), in metal and in stone. To me, the special insight offered by these drawings is in the textures and the colors of the forms.

The texture in the charcoal shading is coarse-grained, but reassuringly intrinsic and organic, somewhere between finely hewn veiny granite and overlapping patterns in brushed metal. It conveys an agnosticism, or perhaps an ambiguity, in the envisaged surface skin of a physical monument that would follow in the likeness of each sketch. Or maybe it indicates an artist’s sentiment that the physical piece can be effected in one of a number of materials or finishes, each with an individual and significant reason for being.

As far as I know, most of Mr. Ferrari’s sculptures during the period of the drawings are generally of a single material (metal or stone), or sometimes two contrasting materials—in either case, with the natural hues of the materials honored—monochromatic and hard. Thus, the drawings, with their polychromatic strokes, whether signifying levity or profundity, are a surprise and a revelation. They suggest to me that perhaps within the stark materials and finishes candidly exposed in the works of the period, there were also deeply imbued inner voices, and purely imaged gestures of color, for us to conceptualize and perceive on our own.

These drawings are highly expressive in their own right, but their relationship with—and enlightenment of—Virginio Ferrari’s larger body of important work, make them incredibly cherished to me.