As I was posting the last entry, on expressing myself without words, it occurred to me that that’s really what art is, or at least attempts to be (putting aside for the moment the art of writing, whether prose or poetry). Why did it not occur to me as I was actually writing the entry, while in Marfa? Quite simply, because I don’t consider myself an artist. I think it is up to the individual to determine whether he (or she*) is an artist—whether his (or her) work should be called “art”. An artist must believe in his work, either the output or even just the process. I am not there, yet—not with my picture taking, photo editing, or any other graphical expression (especially drawing, which I have always been very uncomfortable with). Even though I really do like some of the pieces that I have produced, and other people have said they appreciate them as well, I tend to consider my process and output as “craft” or “design”.

The reason I am so cagey about this distinction is, I think, because I have great reverence for those who live and breathe a high level of commitment to their vision, ideas, and process. Those who have created or uncovered an expression that is individual and heartfelt—an expression that is able to reach others and affect them. Those are the true artists, to me.

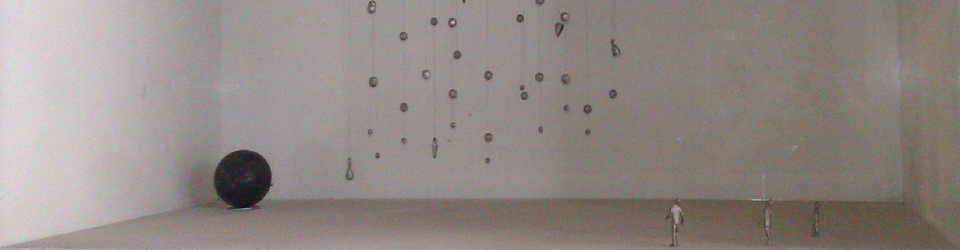

I actually have a wonderful ongoing email conversation about the relationship between words and art with one of those true artists, my friend Raphael Fodde. He has given me permission to reprint a few excerpts from our dialog. We got onto the topic originally as I was acquiring various pieces from him (which I will present pictures of, in a later posting). The impact of seeing a new work for the first time can be profound for me. More than once, I have told him that the unwrapping of a particular piece left me “(almost) speechless”, and then I would proceed to write a paragraph (or two, or three) on the experience. Here is one of my responses to his commendation of my use of words in expressing my appreciation of his work:

As you can tell, I try and choose words carefully to convey my thoughts and feelings, but of course words are imperfect mechanisms for representing things as transcendental as human emotions and philosophies and individual perceptions. However, words are part of our repertoire for personal expression—along with a gaze or voice inflection or touch—and for better or worse, written words are the mechanism often used when communicating over distances (of time or place). The wonderful part is that over time, these imperfect individual representations of ourselves (such as words) cumulatively allow us to get to know (and be known by) the people who interest us and concern us and appeal to us. We start to truly feel and be affected by the emotions and beliefs and viewpoints that originated in the other person. It is important to realize in matters of aesthetics—whether it be art or music or food or wine or poetry or literature or dance—that the words we use to talk about them are incomplete and imprecise, and never worthy substitutes. Instead, they are meant to get others to understand by proxy what we feel deeply on the inside. Words can certainly be powerful, if used effectively, though sometimes a single tear can convey more than an entire book.

Even though I am very self-conscious of my over-reliance on wordiness, I clearly understand the utility of words and don’t discount it. I have conflicting and paradoxical feelings about whether language or contemplation is the more evolved defining feature of human beings (at least, for me). Of course, the two are not at odds, and merely represent left- and right-brain aspects of who we are and how we work. And as with many things, there is a real beauty when pieces of a whole complement each other, and interact in balance and in harmony. As an example, though Raphael claims to have difficulties in expressing himself in English (his third language), there is a truth and eloquence in his use of words in describing his works (in this case, a set of abstract monoprints on fine Japanese tissue):

Those prints express my profound belief in prayer and solitude and meditation; my mind [is] empty and tranquil and my thought are all beyond expression of words.

And additionally, on his artistic process:

Printing and printmaking is an art form in itself and I try to get the maximum from color; my compositions they never suggest anything but abstraction, serenity, solitude, prayer; important elements in my daily life.

His words are certainly closer to art and beauty than mine. But I know that he understands the intent and the effort in my words, about art as well as about words themselves. He exonerates me, thus:

I admire your intellectual honesty and I do understand very well how difficult it is to write something meaningful and truthful especially about art.

My response to that is simply to say, “thank you”.

* This is to acknowledge that by “he” I mean the gender-neutral person. There is much discussion about the lack of an appropriate and elegant handling of this in English. I’m not going to attempt to solve that problem here. I know some people will not like my primary use of the masculine as a stand-in, but that is what’s easiest and most natural (least affected) for me. I mean no harm or disrespect. Others will handle this differently, many to a wider level of acceptance, I would think. Note (and please believe) that I work at having to resort to this fallback as little as possible—an imposition to free expression I wish didn’t exist in English. I consider this a serious topic, which I many discuss at greater length in a future post.

Pingback: The Art of Virginio Ferrari (Part 1) | semelinvita